📖 Pressure vessels: fundamentals, formulas, and derivations

📖 Pressure Vessels: Basics, Stresses, and Formulas

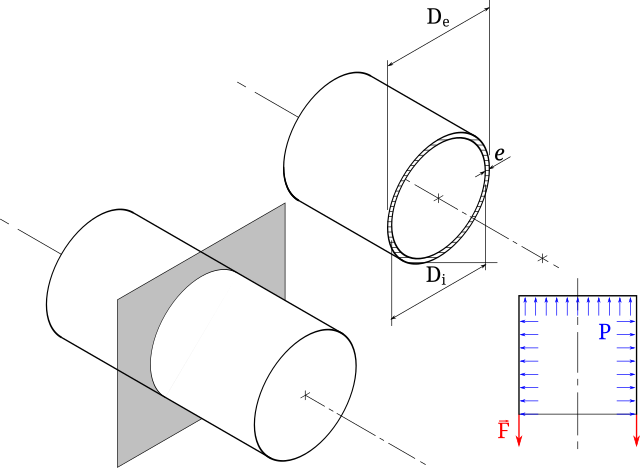

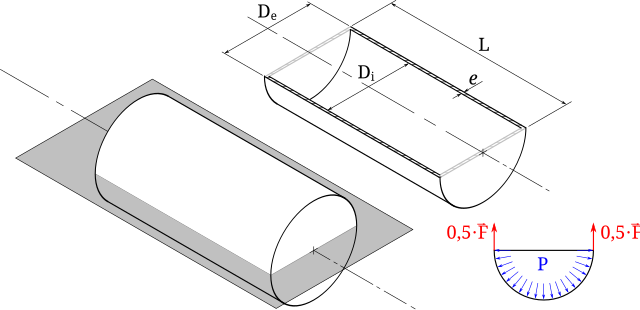

A pressure vessel is simply a container that holds fluids (liquids or gases) at a pressure different from the surrounding atmosphere. Common shapes are cylinders with hemispherical or elliptical heads, because these shapes spread the pressure more evenly. Designing a safe vessel means balancing many factors: the internal pressure, the vessel’s size and thickness, the strength of the material, how it’s made (welds, joints), corrosion allowance, temperature effects, and following design codes like ASME BPVC.

🔑 Key symbols and assumptions

- p = internal pressure

- ri = inner radius

- ro = outer radius

- t = wall thickness = \(r_o - r_i\)

- D = inner diameter = \(2r_i\)

- σh = hoop (circumferential) stress

- σl = longitudinal (axial) stress

- σr = radial stress

- σallow = allowable stress of the material

- Thin wall rule: if \(t/r_i \leq 0.1\), stresses are almost uniform → use thin‑wall formulas.

- Thick wall rule: if \(t/r_i > 0.1\), stresses vary across thickness → use Lame’s equations.

🟢 Thin‑walled cylinder stresses

Hoop (circumferential) stress

Idea: Internal pressure tries to split the cylinder open along its length. The wall resists this by developing hoop tension.

Derivation (simplified):

- Cut the cylinder lengthwise → pressure pushes the two halves apart.

- Force from pressure = pressure × projected area.

- Resisting force = hoop stress × wall area on both sides.

- Balance gives the formula above.

Longitudinal (axial) stress

Idea: Pressure pushes on the end caps, and the cylindrical wall must hold this load in the axial direction.

Radial stress

\[ \sigma_r \approx -p \text{ at the inner wall, dropping to } 0 \text{ at the outer wall} \]

Because the wall is thin, this stress is small compared to hoop and longitudinal stresses, so it’s usually ignored in thin‑wall design.

Design check (thin wall)

\[ \sigma_h \leq \sigma_{allow}, \qquad \sigma_l \leq \sigma_{allow} \]

🟡 Thick‑walled cylinder stresses (Lame’s theory)

When the wall is not thin, stresses vary across the thickness. We use Lame’s equations from elasticity theory.

\[ \sigma_r(r) = A - \frac{B}{r^2}, \qquad \sigma_\theta(r) = A + \frac{B}{r^2} \]

Boundary conditions:

\[ \sigma_r(r_i) = -p_i, \qquad \sigma_r(r_o) = -p_o \]

Constants:

\[ A = \frac{p_o r_o^2 - p_i r_i^2}{r_o^2 - r_i^2}, \qquad B = \frac{(p_o - p_i) r_o^2 r_i^2}{r_o^2 - r_i^2} \]

Final stresses:

\[ \sigma_\theta(r) = A + \frac{B}{r^2}, \qquad \sigma_r(r) = A - \frac{B}{r^2} \]

- At the inner wall (\(r = r_i\)): hoop stress is maximum.

- At the outer wall (\(r = r_o\)): hoop stress is smaller.

- Radial stress = \(-p_i\) at inside, \(-p_o\) at outside.

Special case: external pressure

If outside pressure is greater than inside, stresses are compressive. In that case, buckling may control the design instead of yielding.

Design check (thick wall)

- Check that hoop stress everywhere ≤ allowable stress.

- Often the maximum hoop stress at the inner wall governs.

- For safety, sometimes use failure theories like von Mises:

\[ \sigma_{vM} = \sqrt{\sigma_\theta^2 + \sigma_r^2 + \sigma_l^2 - \sigma_\theta\sigma_r - \sigma_r\sigma_l - \sigma_l\sigma_\theta} \]

🔵 Heads and longitudinal stress

- Flat heads: carry high stresses, usually need thicker plates.

- Hemispherical heads: best shape, stresses are uniform and thickness can be less.

- Ellipsoidal/Torispherical heads: compromise between flat and hemispherical.

- Longitudinal stress (thin wall):

\[ \sigma_l = \frac{p r_i}{2t} \]

⚙️ Practical design notes

- Allowable stress: comes from material strength, reduced by safety factors and temperature effects.

- Corrosion allowance: extra thickness added, not counted in stress calculations.

- Weld efficiency: joints may be weaker, so effective thickness is reduced by efficiency factor \(E\).

- Testing: vessels are hydrostatically tested at higher than design pressure.

- Openings/nozzles: need reinforcement to avoid stress concentration.

- Thin vs thick choice: check \(t/r_i\). If close to 0.1, use thick‑wall formulas for safety.

📌 Summary of core equations

- Thin wall hoop: \(\sigma_h = \frac{p r_i}{t}\)

- Thin wall longitudinal:

\[ \sigma_l = \frac{p r_i}{2t} \]

- Thick wall hoop:

\[ \sigma_\theta(r) = A + \frac{B}{r^2}, \quad A = \frac{p_o r_o^2 - p_i r_i^2}{r_o^2 - r_i^2}, \quad B = \frac{(p_o - p_i) r_o^2 r_i^2}{r_o^2 - r_i^2} \]

- Thick wall radial:

\[ \sigma_r(r) = A - \frac{B}{r^2} \]

🧮 Worked Example (Thin Wall)

Suppose a vessel has internal pressure \(p = 2 \, \text{MPa}\), inner radius \(r_i = 0.5 \, \text{m}\), and thickness \(t = 20 \, \text{mm} = 0.02 \, \text{m}\).

- Hoop stress: \[ \sigma_h = \frac{p r_i}{t} = \frac{2 \times 10^6 \times 0.5}{0.02} = 50 \times 10^6 \, \text{Pa} = 50 \, \text{MPa} \]

- Longitudinal stress: \[ \sigma_l = \frac{p r_i}{2t} = \frac{2 \times 10^6 \times 0.5}{0.04} = 25 \times 10^6 \, \text{Pa} = 25 \, \text{MPa} \]

If the material’s allowable stress is \(150 \, \text{MPa}\), both stresses are within safe limits.

🧮 Worked Example (Thick Wall)

For a cylinder with \(r_i = 0.5 \, \text{m}\), \(r_o = 0.7 \, \text{m}\), internal pressure \(p_i = 5 \, \text{MPa}\), and external pressure \(p_o = 0\):

- Constants: \[ A = \frac{0 \cdot 0.7^2 - 5 \times 10^6 \cdot 0.5^2}{0.7^2 - 0.5^2}, \quad B = \frac{(0 - 5 \times 10^6) \cdot 0.7^2 \cdot 0.5^2}{0.7^2 - 0.5^2} \]

- Hoop stress at inner wall (\(r = r_i\)) is maximum: \[ \sigma_\theta(r_i) = A + \frac{B}{r_i^2} \]

- Radial stress at inner wall: \[ \sigma_r(r_i) = -p_i = -5 \, \text{MPa} \]

This shows how stresses vary across the thickness, unlike the uniform thin‑wall case.

✅ Takeaways

- Thin‑wall formulas are simple and good for quick checks when \(t/r_i \leq 0.1\).

- Thick‑wall (Lame’s) equations are needed when the wall is relatively thick.

- Hoop stress is usually the largest and most critical for design.

- Always compare calculated stresses with the material’s allowable stress, including safety factors.